British Lichens

|

Lichens are 'dual' organisms. They consist of two (or more) different life-forms living together symbiotically in a more-or-less

well defined body or thallus.

The main partner is the fungus or mycobiont. The other partner is a green alga or a cyanobacterium (the photobiont).

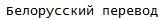

Many cyanobacteria are able to fix nitrogen which is an essential nutrient. In 10% of lichens (e.g. Collema and Leptogium)

the photobiont is a cyanobacterium. The nutritional benefits of having a nitrogen fixing capability is why some lichens, where the

primary photobiont is a green alga, have evolved separate structures called cephalodia which contain cyanobacteria (the secondary photobiont).

So for these lichens there are three partners in the symbiosis.

Lichens are named after the fungal partner.

Placopsis gelida

The fungal partner provides a cosy, sheltered environment for the alga, protecting it to some extent from the elements and

providing mineral nutrients. The actual benefits to the alga or cyanobacterium are debatable but the obvious advantage for

the fungus is the in-house food factory provided by the photobiont. The photobiont partner is more than simply an imprisoned food-slave, however.

It is such a closely evolved alliance that the fungus is dependant on the presence of the photobiont for its shape and structure.

If the fungal partner is isolated and grown on an agar plate it forms a shapeless, infertile blob.

Below is a leafy lichen (tree lungwort Lobaria pulmonaria) cut open to show what is inside. The green algal layer can be

clearly seen at the top of the section with a white algae-free zone below consisting of just fungal hyphae. The middle layer of the thallus is the medulla.

There is also a very thin upper and lower cortex and a layer of rhizines on the lower surface which attaches the lichen to the substrate.

There are four basic lichen growth forms:-

Crustose lichens |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Crustose lichens grow completely attached to the substrate. The main body of the lichen is called the thallus

and there is usually a distinct layer of prothallus between the thallus and the substrate (a bit like a carpet underlay). |

|||

| Areolate The lichen thallus is initially made up of separate lumps growing on the prothallus. These lumps often grow together to produce a continuous cracked surface. The prothallus is often visible between the cracks.  Protoparmelia ochrococca |

Rimose The thallus is initially continuous but becomes cracked into irregularly- shaped and sized pieces.  Lecanora rupicola |

Placodioid The margin of the thallus is formed into radiating lobes which are attached directly to the substrate.  Caloplaca flavescens |

Leprose The lichen thallus does not have a cortex even when young but consists entirely of tiny, fluffy granules. made up of fungus and algae.  Lepraria nivalis |

Squamulose lichens |

|||

|

Squamules are scale-like outgrowths. The lower surface doesn't have a cortex.

They can be very small and sometimes difficult to tell apart from a crustose growth form. |

|||

Normandina pulchella |

Squamarina cartilaginea |

Lopadium disciforme |

Catapyrenium cinereum |

Foliose lichens |

|||

|

Leaf-like lichens where the upper and lower surfaces are distinctly different. Both surfaces are corticate (except in Peltigera).

Usually attached to the substrate by outgrowths of the lower surface such as rhizines or hapters. |

|||

| Foliose The lobes have multiple attachment points such as hundreds of rhizines. |

Umbilicate The lobes are attached by a single stalk or umbilicus. |

||

Flavoparmelia caperata |

Peltigera hymenina |

Umbilicaria torrefacta |

Lasallia pustulata |

| Foliose:- jelly lichens The photobiont is a cyanobacterium. Lobes often swell markedly when wet. |

|

||

Collema auriforme Collema auriforme

|

Leptogium gelatinosum Leptogium gelatinosum

|

||

Fruticose lichens |

|||

|

Shrubby, branched, beard-like or strap-shaped lichens. The branches are rounded or flattened

but both sides are similar (not different upper and lower surfaces). |

|||

| Cup lichens Stick or goblet-like podetia growing out of a crustose or squamulose basal thallus. Often with red or brown reproductive structures on the end of the podetia.  Cladonia pocillum |

Shruby lichens A branched and bushy lichen where the basal thallus disappears very early.  Cladonia portentosa |

Beard lichens Erect or pendent, branched lichens with a tough central core.  Usnea subfloridana |

Hair lichens Pendant, thin, branched lichens without a central core.  Bryoria fuscescens |

Most lichens reproduce sexually by the production of spores but vegetative reproduction is also very common.

Many species use both methods.

Sexual reproduction involves the process of genetic recombination which enables genetic stability to be maintained within the population whilst allowing variation. But there is a slight problem with spores:- A spore represents just a fungal propagule and to become a lichen the germinating spore has to re-lichenise. The spore must germinate in a suitable location and find an algal cell of an appropriate species in order to start a new lichen. Whereas a vegetative propagule already consists of both fungal and algal partners and only has to land and stay put in a favourable location in order to start growing.

Most lichens belong to the Phylum Ascomycota in which the spores are made inside a sac-like structure or ascus (plural asci).

The asci are contained within a "fruiting body" or ascoma (plural acomata). These ascomata occur in a wide variety of different shapes

and colours but there are two distinct types:-

There are also a few lichens which belong to the Phylum Basidiomycota in which the spores are produced on the outside of a cell called

a basidium (pl. basidia). For these lichens the spore-bearing body is called a basidioma (pl. basidiomata).

Although technically incorrect, many of us simply refer to them all as "fruits"!

Some lichen genera such as Lepraria and Thamnolia have never been found fertile.

Types of spore-producing bodies:- |

|||

| Perithecia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Tiny flask-shaped structures containing asci. When mature the spores are extruded through the central pore or ostiole. |

|||

Thelidium papulare |

Thelocarpon olivaceum |

||

| Apothecia | |||

| The layer of spore-containing asci is usually uncovered and visible. |

|||

| Lecanorine With a thalline margin which contains algae and is the same colour as the lichen thallus.  Lecanora pulicaris |

Lecideine Without a thalline margin but with a 'proper' margin which is usually the same colour as the central disc.  Lecidella elaeochroma |

Arthonioid The apothecia are elongated or star-shaped, immersed and flush with the lichen surface.  Arthonia radiata |

Gyrose The apothecia appear twisted, ropey or ridged.  Umbilicaria cylindrica |

| Lirellate Elongated and/or branched.  Graphina anguina |

Pin lichens With a powdery mass of spores on top  Chaenotheca bruneola |

Podetia Twigs with apothecia on top.

Cladonia polydactyla Cladonia gracilis |

|

| Basidiomata |

|||

| Mushroom-fruited lichens. |

|||

Lichenomphalia umbellifera Thallus |

Lichenomphalia hudsoniana Thallus |

||

|

Because lichens are so varied in appearance it is easy to mistake them for other life forms. So here are some non-lichen examples. |

|||

Free-living Trentepohlia algae. |

Algal "gunge" that covers twigs and rocks in areas with high Nitrogen deposition. |

Bark fungus. Easily mistaken for lirellate lichens but have no lichenized thallus. |

Glue fungus on hazel Hymenochaete corrugata. |

Cyanobacteria Nostoc commune. |

Moth with lichen camouflage Merveille de jour (Unmistakable but interesting). |

||

Types of vegetative reproductive structures:-Vegetative propagules get dispersed by wind and rain and creatures great, small, slimey, feathered or furry. If one ends up somewhere good - that's the next generation started. |

|||

| Soredia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Soredia are tiny fluffy parcels of fungal hyphae and algal cells without a cortex

(think of peas mixed with spaghetti, only smaller - around 1/20th mm). |

|||

|

|

|

|

| Isidia | |||

| Isidia are outgrowths of the lichen body containing fungal hyphae and algal cells with a smooth cortical surface

(like a pea and spaghetti pasty?). |

|||

|

|

|

|

Lichens add another layer of diversity and beauty to our environment with their different colours and shapes. A landscape without lichens on the rocks, walls, fences and trees would be so much less interesting. Photographers, artists (and poets) have been inspired by the beautiful patterns that lichens make - the Lichenscapes page has some great examples.

Lichens provide shelter and/or food for a very wide variety of invertebrates, such as mites, molluscs, spiders and moths which are near the bottom of the food chain. A woodland rich in lichens has been shown to have a far greater diversity of other wildlife than a woodland where the trunks and branches are relatively bare. Small birds (chaffinch, hawfinch, goldcrest and long-tailed tit) use lichen fragments to camouflage their nests.

They are excellent barometers of air quality, environmental management and ecological value.

Many lichens are sensitive to airborne pollutants such as sulphur dioxide, oxides of nitrogen, NPK fertilizer and ammonia etc. Lichen distribution data can be used to indicate pollution problems.

Some species are highly adapted to a particular ecological niche such as a dry underhang on an old oak trunk or a dried up wound track from a broken branch. Also these species are often poor colonisers. This means that their existence at a particular location is dependent on the continuous local availability of that particular niche. Lichens can therefore be used to infer continuity of management and as part of the evidence to determine the age of a woodland. This has led to the development of Indices of Ecological Continuity for various woodland types where the total number of certain indicator species is used as a measure of the conservation importance of that woodland.

A good site for rare lichens is also likely to be rich in other things such as invertebrates, bryophytes and higher plants. In contrast, higher plants are not such good indicators; if you clear-fell an ancient woodland, almost all the herbs and trees will still survive. But the rare lichens, bryophytes and invertebrates will almost all disappear, leaving only common, weedy species, and it may take many centuries for them to return (if ever), depending on how far it is to the next population.

To start out all you really need is a hand lens. For a modest investment it is amazing what facinating and beautiful detail can be revealed with a simple x10 hand lens.

The next step usually involves getting hold of a dissecting microscope, to see fine details more easily. You will also need a variety of chemicals to carry out 'spot tests'. Spot tests are where a tiny drop of chemical is applied to parts of the lichen. The most common chemicals are bleach (Calcium or Sodium hypochlorite or 'C' for short - cheap, thin bleach is best), Potasium hydroxide (K), Paraphenylene diamine (Pd) and Iodine (I). These chemicals produce a variety of different colours (or no reaction) depending on the presence of various lichen compounds which are characteristic to different species. You do have to be careful when using and handling these chemicals for obvious reasons. Pd is considered to be (probably mildly) carcinogenic so I always open the jar outside to let the built up fumes escape before taking a very small amount to make up a fresh solution.

To get fully into lichens you do need a compound microscope in order to examine tiny details such as the size and shape of spores etc. Obviously, how much you want to get involved with lichenology is completely up to you. But you don't need to be an expert to join the British Lichen Society. The BLS is made up of a wide range of abilities and degrees of involvement. An interest in the subject is all you need. But there is no better way to learn than to spend time with fellow enthusiasts.

There are 1873 species listed in The Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland. However, some of these are considered to be extinct in the British Isles so the actual figure is around 1800. But more are still being discovered each year, either new to the region or new to science. This compares with about 1760 species of native vascular plant.

The world lichen list probably stands at around 17,000 although it is difficult to be precise since many regions have not been thoroughly searched.

Since lichens are primarily composed of soft tissues they are very rarely found as fossils. The earliest evidence comes from a 600 million year old lichen-like fossil from China. The next record comes from our own Rhynie chert (Aberdeenshire) at around 410 MY. The Rhynie chert was formed by a hot spring system and is of world importance for its geology and the exceptionally well preserved animals and plants it contains.

Then there is a long gap where at some stage a recognisable lichen thallus evolved as revealed by leafy or bushy lichen fossils aged around 65 MY (Tertiary period). There is a modern-looking Lobaria fossil dating back 12 - 24 MY from California and many examples of excellently preserved specimens in amber from around the world dating from 55 to 15 MY.